The first Black graduates & Harvard’s report on the Legacy of Slavery4 min read

Reading Time: 4 minutesReading Time: 4 minutesOn the 19th of June, the United States celebrated Juneteenth or Freedom Day, which is a federal holiday commemorating the emancipation of enslaved African-Americans, the day when enslaved Americans in Galveston, Texas, finally learned that they had been free for 2 years. It only became an official holiday in 2021. It is highly important to own up to one’s past and find the courage to speak up.

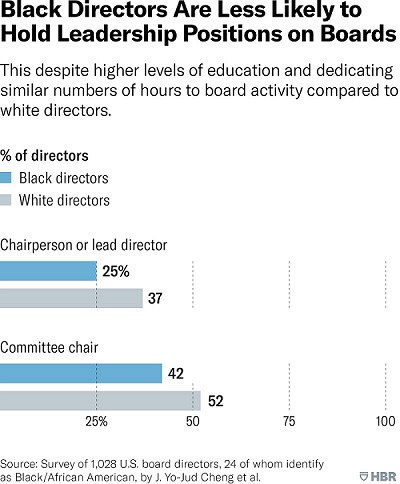

According to Harvard Business Review (HBR), only 7% of U.S. higher education administrators, 8% of managers, and 3.8% of CEOs were Black in 2019. Although these numbers are growing each year and more companies try to diversify their workforce, Black people are still underrepresented when it comes to leadership positions. Despite candidates’ qualifications and investing the same amount of time in their boards’ work, researchers from HBR found out that Black directors are less likely to hold board leadership roles.

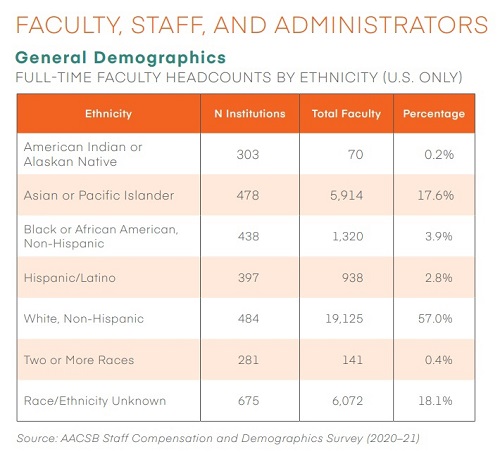

Moreover, according to another report, titled 2021 Business School Data Guide, released by AACSB, in the United States, Black or African American people take only 3.9% of all positions in business schools, while the majority (57%) of the full-time faculty is White. America’s history of discrimination certainly contributes to this disproportionality.

Recently, Harvard University released its report of the Presidential Committee on Harvard & the Legacy of Slavery, which describes the findings of the research on slavery in Harvard’s past. It is stated that between Harvard University’s founding in 1636 and the end of slavery in the Commonwealth in 1783, Harvard faculty, staff, and leaders enslaved more than 70 people, some of whom worked on campus. Slavery within the walls of the university continued until the 19th century. Then, in 1850, Harvard Medical School became a center of science rooted in racial hierarchy and discrimination, which later was labeled as a “race science.” Despite these dark secrets of the university’s history, there was a confrontation about the unfair state of affairs among the students. Throughout the 20th century, Black students resisted marginalization by entering the university and earning their Harvard educations, reshaping the nation. However, the fight was not restricted only to pursuing an education at one of the best universities.

Sarasota interviewed Lillian Lincoln Lambert, the first Black woman to graduate from Harvard Business School (HBS) in 1967, in which Lillian told how education for a Black person was at HBS back in 1967.

Lillian was born in a city much smaller than New York. Her mother graduated from Virginia State University, and her father had only a third-grade education and could not write. Lillian wanted to work as a secretary, but as her high-school diploma could not lead her to this position, she decided to go to Howard University, where she met H. Naylor Fitzhugh. Naylor was the first Black man to graduate from HBS in 1933 and worked as a professor at Howard University. Lillian says that it was he who encouraged her to apply for the MBA program at Harvard Business School and live a better life.

Lillian says that out of 800 students, there were only 18 women and 6 Black people: five men and her. The Black community did not exist at HBS, but Lillian and others tried to change that: they started the African American Student Union, which celebrated its 50th anniversary in 2018, to support other students. Moreover, with their efforts, the school agreed to recruit Black students and promised to go to corporations for scholarship money, which increased the number of Black students next year. It is important that the African American Student Union is still active nowadays, as it provides mentorship for the Black students and gives the feeling of a community.

After Lillian gained her MBA, although she did not have any intention to become an entrepreneur, in 1976, she launched her own business, which grew to a $20 million enterprise. In 2003, Lillian was awarded the Alumni Achievement Award, the highest honor for alumni for being an exemplary role model in business and community. Having such a brilliant alumnus, Harvard has applied all its efforts to support its own students and provide a better future for them.

Thus, at the end of the report on the Legacy of Slavery, researchers from Harvard University drive with a few recommendations for the educational institution itself. They recommend the university support descendant communities, honor enslaved people through memorialization and research, and by providing financial support for the production and distribution of information regarding Harvard’s ties to slavery. Moreover, it is recommended to develop partnerships with Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs), for instance, by funding visiting fellowships. One of the main steps in admitting the university’s past would be an identification of direct descendants of enslaved individuals who labored on Harvard’s campus and support provided for them through dialogue, information sharing, and educational help. Finally, it is advised to create a Legacy of Slavery Fund to support the implementation of these recommendations. Later on, Harvard University promised to allocate $100 million to address the past and implement all the recommendations made in the discussed report.